Getting started with Content Credentials

This is a technical introduction to the Content Authenticity Initiative (CAI) open-source SDK that provides initial context and an overview of the technical aspects of implementing CAI solutions.

The CAI open-source SDK is fully compliant with the C2PA specification, but it's important to note that the specification is more general than the SDK, which doesn't support every feature in the specification.

Important terminology

To understand how CAI works, you need to understand some basic vocabulary. Having this vocabulary makes it easier to discuss CAI's technical aspects. The definitions below are summarized and slightly simplified from the Glossary in the C2PA specification. This document is meant to convey the general concepts and may not cover all technical details or edge cases that the specification addresses.

Let's start with a broad definition of content provenance which means information on the creation, authorship, and editing of a digital asset such as an image. Content Credentials include this provenance information, along with the cryptographic means to authenticate that the information is correctly tied to the content and is unchanged from when it was originally added. Sometimes these two terms are used to loosely mean the same thing: Technology to verify the origin and history of a digital asset.

In practice, Content Credentials are kept in a C2PA manifest store, and the CAI SDK works with that. A manifest store consists of one or more individual manifests, each containing information about the asset. The most recently-added manifest is called the active manifest. The active manifest has content bindings that can be validated with the asset; that is, it's hashed with the asset to ensure its validity.

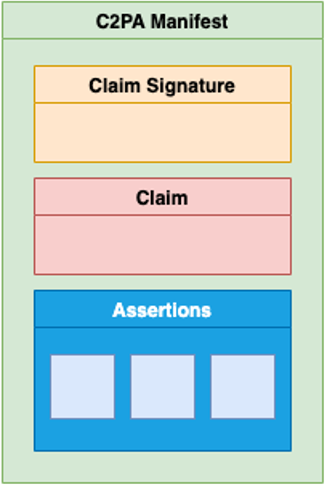

As illustrated below, the manifest contains assertions about the asset's creation and history, wrapped up with additional information into entities called claims that are digitally signed with an actor's private key (the claim signature).

Now, let's drill down a bit to clarify some of these terms.

Actor: A human or hardware or software product. For example, a camera, image editing software, cloud service, or the person using such tools.

Asset: A digital media file or stream of data of certain specific image, video, or audio formats. A composed asset generalizes this concept, for example an image superimposed on top of another image.

Action: An operation that an actor performs on an asset. For example, "create," "embed," or "change contrast."

Assertion: Part of the manifest "asserted" by an actor that contains data about an asset's creation, authorship, how it's been edited, and other relevant information. For example, an assertion might be "change image contrast." For a list of standard C2PA assertions, see the C2PA Specification.

Certificate Authority (CA): A trusted third party that verifies the identity of an organization applying for a digital certificate. After verifying the organization's identity, the CA issues a certificate and binds the organization's identity to a public key. A digital certificate can be trusted because it is chained to the CA's root certificate.

Certificate (public key certificate or digital certificate): An electronic document that vouches for the holder's identity. Like a passport, the certificate is issued by a trusted third party (the CA), cannot be forged, and contains identifying information.

Claim: Digitally-signed and tamper-evident data that references a set of assertions by one or more actors, concerning an asset, and the information necessary to represent the content binding. For example, a claim could specify that a particular image was edited by John Doe using Product X on 05/08/2021 at 11am to change the image contrast.

Claim signature: Part of the manifest that is the digital signature on the claim using an actor's private key.

Content binding: Information that associates digital content to a specific manifest associated with a specific asset, either as a hard binding or a soft binding.

Manifest (C2PA manifest): Information about the provenance of an asset based on the combination of:

- One or more assertions (including content bindings).

- A single claim.

- A claim signature.

Manifest store: A collection of manifests associated with asset. The most recent manifest in the manifest store is the active manifest, which has the set of content bindings that are hashed with the asset and thus can be validated.

For more definitions and detail, see the C2PA specification.

How it works

A manifest is a binary data structure that describes the history and identity data attached to digital asset. The CAI SDK enables applications and websites to attach a manifest to an asset and display it when requested. This helps viewers to understand the origin and evolution of the asset.

Although the manifest structure described in the C2PA specification is a complex binary structure, the CAI SDK works with a JSON manifest format that's easier to understand and use. It's essentially a declarative language for representing and creating a manifest in binary format. For more information on the CAI JSON manifest, see Working with manifests.

The CAI uses cryptographic asset hashing to provide verifiable, tamper-evident signatures to indicate that the asset and metadata haven't been altered since the asset was published with the attached manifest. This means that a hash function converts the digital asset data to a unique "fingerprint," which is signed using a certificate. Once the credentials are signed, if the asset is changed then its fingerprint also changes. That's why it's called "tamper evident." You're not prevented from changing an image that has Content Credentials, but if you do, the credentials are no longer valid unless you change it using a tool that updates and re-hashes the credentials, along with a timestamp and optionally a description of what changed. The C2PA specification refers to this as hard binding.

Introduction to public key infrastructure

For authentication, C2PA uses public key infrastructure (PKI) technology, a widely used international standard: The same technology used to secure websites using HTTPS, to secure email using S/MIME, and for many other digital security purposes. C2PA uses the international X.509 standard, the most common format for public key certificates.

A signed digital certificate verifies the authenticity of an entity, such as a server, a client, or an application. You typically purchase a certificate from a third-party certificate authority. A certificate can contain the following information to verify the identity of an entity:

- Organizational information that uniquely identifies the owner of the certificate, such as organizational name and address. You supply this information when you get the certificate.

- Public key: The receiver of the certificate uses the public key to decipher encrypted data sent by the certificate owner to verify its identity. A public key has a corresponding private key used for encryption.

- Name of the CA that uniquely identifies the issuer of the certificate.

- Digital signature of the CA that verifies its authenticity. The corresponding CA certificate compares the signature to verify that the certificate originated from a trusted certificate authority.

Signing and certificates

A manifest attached to an asset contains information about the origin of the asset, such as the name of the tool that created it (for example, Photoshop) and the name of the actor who created or modified it. Then editing the asset using a supporting tool or site adds a new manifest (indicating the actions taken) that is signed with the certificate of the tool/site; this becomes the active manifest, which then references any prior manifests as ingredients.

Each manifest is digitally signed with the application's or client's credentials. To enable validation of the credentials, the manifest also includes the signing certificate chain. The "chain" of certificates starts with the certificate from the last tool that signed the manifest (known as the "end-entity") followed by the certificate that signed it, and so on, back to the original CA issuer on the trust list. A user can trust that the manifest is valid because there is a "trust chain" that goes back to a trusted root certificate authority. That's why you need to acquire a security certificate from a legitimate certificate authority.

In practice, to use a certificate with the CAI SDK, follow this process:

- Purchase security credentials (certificate and key) from a certificate authority. Either email protection or document signing certificates are valid.

- Extract the certificate by using a tool such as OpenSSL (for use during development). In production, you should host the private key in a secure environment like a hardware security module (HSM).

- Use one of the supporting CAI libraries or C2PA Tool to sign manifests using the certificate and your private key.

For more information on getting and using certificates, see Signing and certificates.

Trust lists

The C2PA trust list is a curated list of certification authorities (CAs) that are authorized to issue signing certificates for conforming generator products.

Conforming validator products such as the Inspect tool on Adobe Content Authenticity (Beta) use the C2PA trust list to determine whether a Content Credential was issued using a certificate that can be traced back to a CA on the C2PA trust list.

The Verify tool uses the interim trust list to determine which certificates are considered valid. Verify will be updated to use the official C2PA trust list.

Identity

To identify who created or modified an asset, identity needs to be verifiable and bound to an asset and its manifest store.

The Creator Assertions Working Group (CAWG) provides a technical specification for an identity assertion for use in the C2PA ecosystem. For more information, see Reading CAWG identity assertions.

In addition, Adobe tools can use the Connected Accounts service to connect social media accounts such as Behance, Instagram, or Twitter to an identity in a manifest. This service uses OAuth, so a user must be able to log in to an Adobe account to connect it.

Attaching and storing manifest data

Once you've generated a manifest, you must attach it to the asset for it to be useful.

Storing a manifest in file

You can embed a manifest directly in a digital asset (image, audio, or video file). Currently, this is the only approach available to developers other than Adobe, which operates the Content Credentials Cloud store. Adobe tools may both store the manifest in the file and upload it to the cloud.

Embedding a manifest in an asset usually increases the size of the file. Two things contribute to this increase:

- Whether a thumbnail image is stored and its quality. This typically adds around 100KB – 1MB to the size of the file, depending on the quality of the thumbnail.

- The size of the certificate chain: Signing chain and timestamp certificate chain each may be around 10KB.

Storing a manifest in the cloud

In addition to storing the manifest with the asset, Adobe tools use the Adobe Content Credentials Cloud, a public, persistent storage option for attribution and history data. Publishing to this cloud keeps files smaller and makes Content Credentials more resilient, because if stripped from an asset someone can find them by searching with the Inspect tool on Adobe Content Authenticity (Beta). On the other hand, embedding the manifest keeps the file self-contained and means no web access is required to validate.

Currently, Adobe Content Credentials Cloud (ACCC) is only available to Adobe tools, though in the future other credentials clouds may become available if other organizations want to host a credential service. Currently, most manifests will be embedded in assets since ACCC is specific to Adobe.

Displaying manifest data

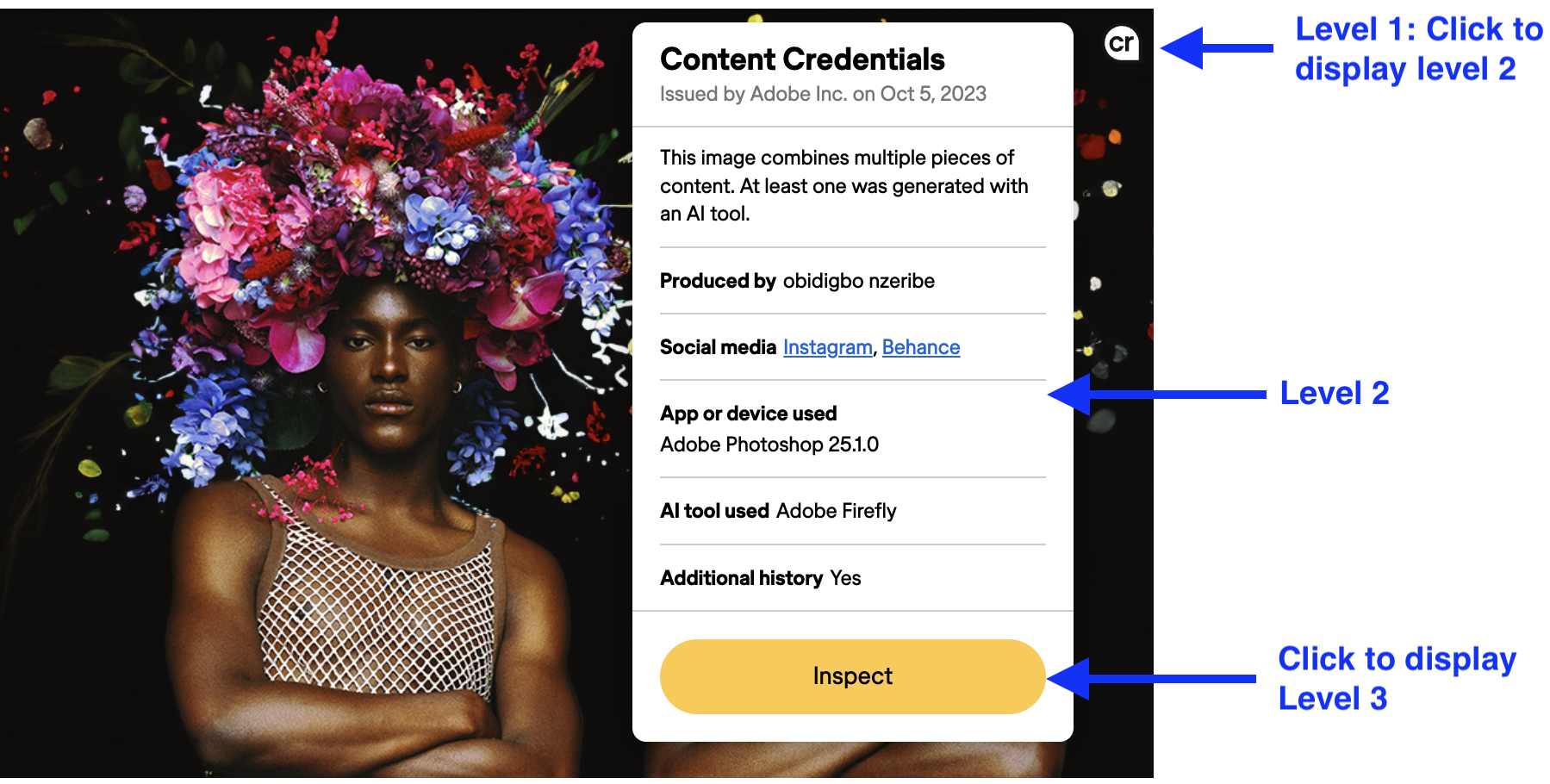

The manifest is only useful to end users if it can be displayed meaningfully in a user interface. How a UI does that is of course up to the designer, but because the full set of manifest data for an asset can be very complex, there are four recommended levels of disclosure:

- Level 1: Indicates that manifest data is present and whether it has been validated.

- Level 2: Summarizes the manifest data enough to describe how the asset came to its current state.

- Level 3: Provides a detailed display of all relevant manifest data, including ingredient manifest. The implementation determines what's relevant and how to display it.

- Level 4: Provides the complete data including full detail of signatures and trust signals, for sophisticated, forensic investigatory use.

The example shown below illustrates one way to implement levels of disclosure:

- The Content Credentials pin

shown over the image indicates that the image has Content Credentials (level 1).

- Clicking on the pin displays level 2 information, and an Inspect button.

- Clicking the Inspect button opens the image on ACA Inpsect that provides level 3 information.

Example uses

Numerous Adobe tools and products implement Content Credentials. For example, you can optionally attach credentials to images you create or modify using Photoshop and Lightroom. Additionally, all images created using the Firefly generative AI tool automatically have attached Content Credentials. Behance displays Content Credentials if they are attached to media shared on the site, and still images provided through Adobe Stock automatically have Content Credentials attached. Other Adobe products also support Content Credentials.

The Inspect tool on Adobe Content Authenticity (Beta) inspects image files and displays their Content Credentials if they exist. See Using ACA Inspect for more information.

Additionally, several other organizations have implemented CAI solutions, including:

- PixelStream: Provides a complete end-to-end C2PA Content Credentials based authenticity platform that encapsulates the entire authenticity lifecycle of an asset from capture/creation, through editing, distribution via CDN, and finally to display.

- ProofMode: Provides an ecosystem of open-source tools and systems, including CAPTURE, a camera app with built-in provenance and authentication for chain-of-custody and VERIFY, a multi-purpose tool to inspect metadata and detect AI in images, audio, and video.

- SmartFrame Technologies: Validating provenance with secure capture to enhance innovative image streaming delivery.

- The New York Times R&D: Using secure sourcing to combat misinformation in news publishing.

For more case studies, see CAI Blog.